This is a picture of the High Street in Sutton in Surrey taken at Christmas, 1908 – which is not all that long ago in the grand scheme of things, but long enough, as it turns out, for almost everything visible in this photograph to have disappeared entirely. Gone are the dignified bunting and proud flags and the banner proclaiming ‘Here we are again’. Gone are the cumbersome means of transport, the fashion, the manners and mannerisms, the solemn lettering, even Robinson’s High Class Teeth (which might be a good thing). But I said ‘almost everything’ has disappeared because there has been one remarkable survival from this picture. It is connected with another of these shops on the right, no. 18: the photography studio of David Knights-Whittome, advertising him as ‘Photographer to His Majesty the King’. It is his business that we have to thank for some 11,000 photographic negatives taken of Sutton’s townsfolk between 1904 and 1918, and it was his photographic eye that recorded the characters of people who knew and walked this frozen High Street when it was living. We have to be grateful also to providence that so much of this collection survived the twentieth century against all the odds, so that it is now possible for them be cleaned, conserved, rehoused, catalogued, digitised, researched and put online by Sutton Archives, with the help of local volunteers and a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund. The banner that announced ‘Here we are again’ in 1908 turns out to have been a message not only for the ordinary Edwardians of Sutton, but for us in the present day. Here they are again indeed.

This is a picture of the High Street in Sutton in Surrey taken at Christmas, 1908 – which is not all that long ago in the grand scheme of things, but long enough, as it turns out, for almost everything visible in this photograph to have disappeared entirely. Gone are the dignified bunting and proud flags and the banner proclaiming ‘Here we are again’. Gone are the cumbersome means of transport, the fashion, the manners and mannerisms, the solemn lettering, even Robinson’s High Class Teeth (which might be a good thing). But I said ‘almost everything’ has disappeared because there has been one remarkable survival from this picture. It is connected with another of these shops on the right, no. 18: the photography studio of David Knights-Whittome, advertising him as ‘Photographer to His Majesty the King’. It is his business that we have to thank for some 11,000 photographic negatives taken of Sutton’s townsfolk between 1904 and 1918, and it was his photographic eye that recorded the characters of people who knew and walked this frozen High Street when it was living. We have to be grateful also to providence that so much of this collection survived the twentieth century against all the odds, so that it is now possible for them be cleaned, conserved, rehoused, catalogued, digitised, researched and put online by Sutton Archives, with the help of local volunteers and a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund. The banner that announced ‘Here we are again’ in 1908 turns out to have been a message not only for the ordinary Edwardians of Sutton, but for us in the present day. Here they are again indeed.

They were ordinary people like Miss Neate who, during her visit to Sutton on the 11th December 1908, might have been able to admire the Christmas decorations if they had been put up, or have thought 1907’s had been better, before she went into Knights-Whittome’s studio to have this photograph taken. They were ordinary people like Mr. E. A. Blacker who had been a sitter the previous February.

For single portraits like this, Knights-Whittome tended to use glass plate negatives. The negative was simply a small rectangle of glass coated in a ‘light-sensitive emulsion of silver salts’. By the time of these photographs they were being mass-produced. Knights-Whittome tended to take several exposures per client, sometimes using a single plate for each shot, as he does here, and sometimes squeezing two onto the same plate, as he did for this client, seen here a year later.

A sitter with a name like Detective Enticknap was perhaps not so ordinary, but a Charles Henry Enticknap was indeed a detective and member of the Metropolitan Police from 1887 to 1913 (his biography is here). When the print had been taken of the negative and the happy customer had left, the plate was numbered and labelled with the sitter’s surname, put in an envelope and placed on shelves and in boxes in the basement of the shop.

|

David Knights-Whittome, 1876-1943, self-portrait

|

This is the man at the heart of the story: David Knights-Whittome, who was born in Greenwich in 1876 and was the seventh child of Joseph Whittome (a warehouseman and Baptist minister) and Eunice Smith. He probably taught himself the art of photography. The Borough Archives at Sutton hold a notebook that he compiled at the age of 18, entitled ‘Secrets of Photography’. There are records of his having worked in Edmonton (North London) and Woking (in Surrey) before he moved to Sutton in 1904. Here he married, in 1907, Sarah Elizabeth Draper, known as Bessie. They had two sons, Maurice and Ronald, born in 1908 and 1912 respectively.

He was also indeed a photographer to the King, as he claimed (if not the only one), obtaining a Royal Warrant of Appointment in 1911 and being one of the official photographers at Prince Edward’s investiture as Prince of Wales at Caernarvon Castle in 1911. His royal subjects included Edward VII, George V and Edward VIII at various ages, and also King Alfonso of Spain, King Manuel of Portugal and Queen Maud of Norway.

To the shop in Sutton, opened in 1904, he added a studio in Epsom in 1911. All the negatives from both studios were kept together in Sutton without any distinction between the series, which means that any photograph from this date onwards could have been taken in either town. This has repercussions for the identification of the sitters.

It seems that in 1918 Knights-Whittome gave up photography as a career altogether. The Sutton and Epsom shops closed, and the family had moved away by 1921 to Wimbledon, then to Bournemouth and finally to retirement in St. Albans, where Knights-Whittome was mayor in 1940. He died in 1943. As for the one-and-a-half tonnes' worth of glass negatives, they had all been left in the basement of 18, High Street, Sutton in 1918… There they would remain for sixty years.

The involvement of the Sutton Borough Archives began in 1978, when June Broughton, the Local Studies Librarian, was contacted by a member of the public about a certain large collection of glass plate negatives in the basement of Linwood Strong optician’s in the High Street… The building was to be demolished to make way for a road-widening scheme (this happened in 1986). So June Broughton and Frank Burgess, a local historian, went to investigate. In the words of Abby Matthews, the current Project Officer for the ‘Past on Glass’ project, ‘they were met with a scene of neglect and damage’.

|

| The state of the collection in the basement of 18, High Street, Sutton, Surrey, in 1978. From the project blog. |

Everything remained much as it had been left, on open shelves in original envelopes, except that some of the shelves had collapsed onto others, and some of the plates had been piled up on top of each other anyway, so they were also bearing their own weight. The inevitable result is shown by the fragments of broken glass visible on the floor.

The plates were moved to Cheam Library as a matter of urgency. Eventually they were transferred to the main civic offices in Sutton and given to the borough by the Knights-Whittome family. However, many of the plates had been broken and, worse still, had suffered water damage in the cellar so that they were stuck in their brown envelopes. On a large number of plates the emulsion was delaminating, or peeling and flaking off the glass, and with it the image itself.

The collection remained in this position for thirty more years. Then in 2014, after lengthy audits and consultation with photographic conservators, a successful application was made to the Heritage Lottery Fund for the preservation of the collection. Nearly £100,000 was awarded so that every plate could be cleaned, rehoused and catalogued, and undergo conservation if necessary. The funds also provided for their comprehensive digitisation, not least so that they could be made public over the Internet. The project was called ‘The Past on Glass’.

The Project Officer, Abby Matthews, and Kath Shawcross, the Borough Archivist, oversee a number of local volunteers who clean, catalogue, rehouse and scan as many plates as they can, sending some for conservation. Some volunteers carry out research on family history websites to try to shed some light on the people in the portraits. Then they are uploaded to the project’s Flickr page, where there are already about 4,000 images.

The collection might have lain for a hundred years awaiting its moment, but in some respects the timing of this new project is perfect. Only in recent years has the technology become readily available for a proper digitisation programme. The same goes for the way in which the Internet can make the collection far more accessible virtually than it ever could have been physically.

As they have done so they have had to contend with all sorts of difficulties. For example, the writing on these envelopes, all scrawled in ink and bled into the poor paper, are still the only source of information for most of the plates: all the ledgers and account books have disappeared. And the information that survives is often incomplete: many surnames are illegible or undated.

The photograph inside might be stuck, or the emulsion flaking, so it has to be done gingerly! Then they have had to catalogue the plates in a way that tries to straighten out Knights-Whittome’s idiosyncratic system of numbering. But all of this is outweighed by the experience of liberating a photograph that has not seen the light of day for a century, and coming face to face with the people and the characters of that vanished age:

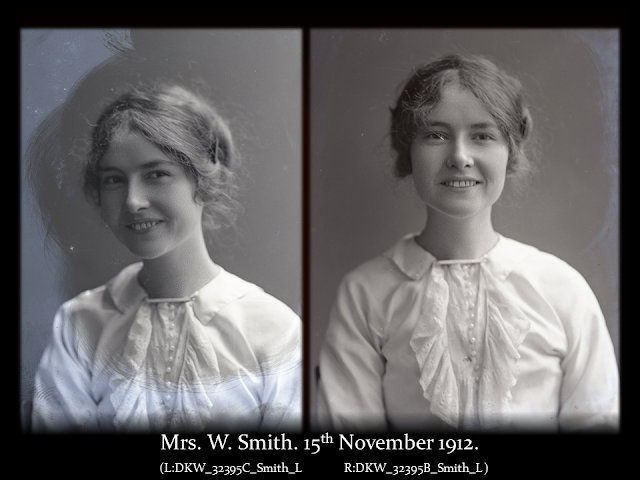

For example, Mrs. W. Smith, photographed on the 15th November, 1912. Abby Matthews (the Project Officer) has noted that the largest category of photographs are single portraits of women, like this. One of the reasons she suggests for this is the First World War, which looms large over this collection in many ways. It would make sense for soldiers who went off to fight to take photographs of their sweethearts with them.

Correspondingly there are many pictures of officers in uniform. This is J. A. Boyd:

The archives assistant at Sutton found that he had enlisted in the 3rd East Lancashire Field Ambulance Corps two years earlier at the age of sixteen, when he was three years underage. He survived the war.

Below is Private Harold Dickson Mims, born in North London in 1896; son of Ernest and Sarah Jane Mims; enlisted as a private in the 5th (City of London) Battalion (London Rifle Brigade); embarked for France in January 1915; promoted to Lieutenant in early 1917; killed in action aged 22 on the 27th September, 1918.

There are group portraits as well. Here is a couple called Bevington, frustratingly with no year given. I had a go at researching this couple but could not find out anything concrete about them. But the advantage of their being on the Internet is that the families themselves are more likely to find them and supply the necessary information.

There are also many photographs of babies and children. This is Baby Bamber on the 10th December 1915:

There are some wonderful characters among the plates. For example, here is Miss Mabuine on the 18th of January, 1907:

…and a few months later the jovial Mr. Fiddyment sat for his portrait. Abby Matthews has pointed out that he must be a working man because of the grime in his hands and his worn jacket: unusual, because working men would not normally have been able to afford to have a photograph taken like this.

Miss Biddulph in an impressive hat on the 2nd September 1912:

And there were pets: Here is Mrs. Henderson and her dog, 5th December 1916:

Knights-Whittome did occasionally venture outside the studio, for instance to take these pictures of classes at the convent school at Carshalton.

And this is Mr. Andrews who, astonishingly enough, was not satisfied with his portrait, and wrote to Knights-Whittome to tell him so. It is not yet clear whether this is the offending or the corrected version:

Great Fell

E. Molesey

Aug 7th 1907

Dear Sir,

I am not at all pleased with the photos. Everyone who has seen them says they are very poor & I must ask you to see what you can do towards bettering them. The one X is all on one side as though the face was badly swollen & twisted. The other is the better of the two & I think can be made to look more natural by turning the nose down & not up as it now is. I am not aware that my nose turns up nor is anyone else who knows me – the head & figure stoops rather too much forward & this can easily be altered when cutting the photo for mount & I think they would look infinitely better if darker about the top of the head – Please adjust these items! Let me have the ½ dozen as soon as you can.

Yours truly,

R.M. Andrews

This goes to show that photographers were in the habit of retouching their work even in those times, mainly by pencil on the reverse of the glass plate. There is a post here on the project blog about Mr Andrews and his exacting standards!

I count myself very fortunate to have been able to volunteer for this project — only for a short time (and I miss going) but enough to cement my decision to pursue a career as an archivist. There are plenty of others who have also found it tremendously rewarding. Recent good news has been that the project has received a second much-needed grant from Lottery Fund. This means hopefully that the work can be brought to completion.

Of course, this post is a feeble attempt to do justice to this astonishing collection, which throws open not a different era but a vanished civilisation. There are weddings, grown men in fancy dress, clergymen, schoolchildren and students, and no end of babies and dogs. There are enigmatic people, too, whose gaze meets ours unsettlingly across the gulf of the twentieth century. There they are again, full of quirky nooks and eccentric crannies, spirited, upright and full of life, just as we are now.